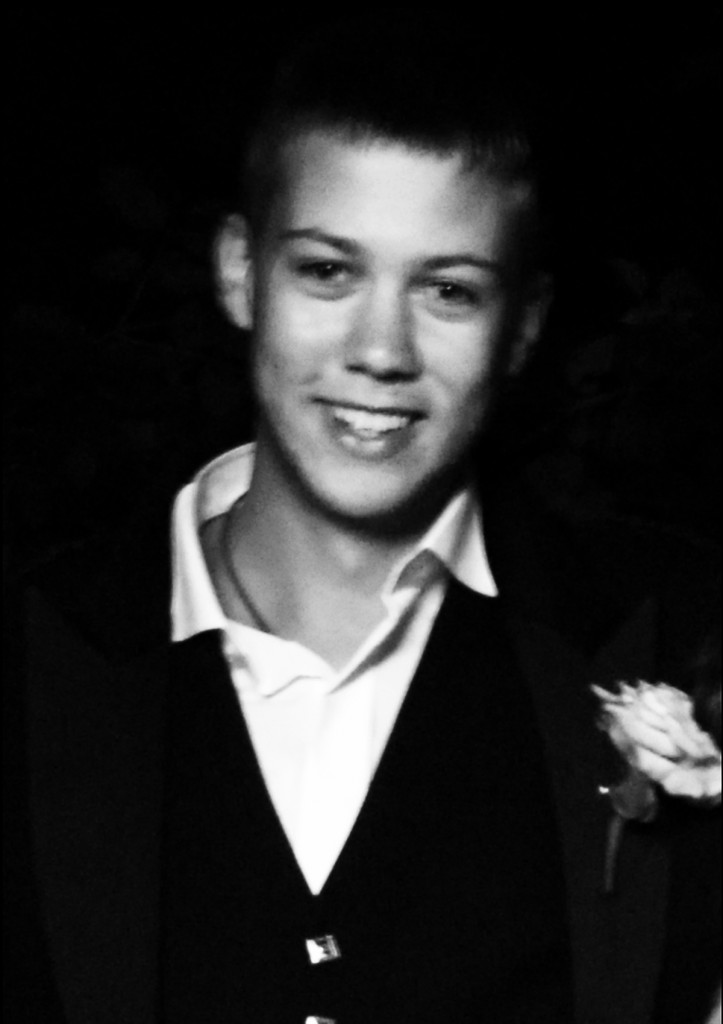

Mourning and Transformation — Sifting for Gold - A mourning father tries to make sense of his experience through an academic analysis of grief.

The following is an analysis by Jimmy Edmonds of a recent thesis “Mourning and Transformation — Sifting for Gold” by Fiona Rodman (MA University of Middlesex). Jimmy attempts to understand some of Fiona’s ideas as they relate to his own experience with loss and grieving of his son, Joshua.

After I had read Fiona’s thesis for the first time, I had a real sense of a burden lessened; that the grief I had felt for [my late son] Josh was less complicated and more natural than I had previously supposed it to be. Here was an account of the mourning process, told not just from a theoretical perspective, but illuminated with the real insight from her own personal experience. Fiona’s mother died at an early age, she endured the break up of a long marriage, and witnessed her father lose his own battle to dementia. Her journey — her different journeys of coming to terms with these deaths inform her conclusions of what it means to mourn.

To a certain extent I think I have been caught up with what I thought society had expected of me in dealing with Josh’s death… how to behave, what to say, what to feel. How could it be otherwise? Even in this modern age with its fast changing moral and ethical codes, we are so influenced by long standing attitudes to death and its aftermath, that it seems the only right thing to do is to rely on the consensus and on traditional ideas when we are trying to find a way forward on the journey through grief.

In her essay, Fiona explores the connections and the tensions between personal emotions and public expectations. What I’d like to do here is to try to extract from this necessarily lengthy and rigorously academic piece of work, some of her basic ideas that have helped me understand a little more some of the thoughts and feelings we have all been experiencing since Josh died.

“Sifting for Gold” is concerned with the transformative power of grief. Another’s death, particularly someone who is close to us and someone we love, is always a life-changing event. This might seem so obvious, it shouldn’t need saying, but until Josh died, I hadn’t fully understood how difficult it is for many people to accept this change. Fear of our own mortality certainly kicks in; confronted with the fact of another’s death, or another person’s loss, our thoughts about the inevitability of our own death become so uncomfortable, they prevent us from truly seeing or at least acknowledging another’s pain. As a family, we have all experienced having to skirt round the issue of Joshua’s death, for the sake of not embarrassing a friend or an acquaintance.

Yes, it’s weird, but to hide one’s own feelings for the sake of another’s shame is, I have found, a common occurrence. All too often, we hear that people just don’t know what to say, but this becomes understandable when you realize that it’s not just that another’s death is such an ominous reminder, but that the bereaved have indeed undergone a fundamental change. How that change is managed (or not) is the subject of Fiona’s essay.

Her own mother passed away when Fiona was in her early twenties. But it wasn’t until many years later that she discovered that she had not properly mourned her mother’s death. At the time, she had felt dislocated and adrift and that there were deep constraints on sharing her feelings with her immediate family. “We were close,” she writes, “as if clinging on to a shipwreck together. We could not however, weep together, fall apart, sob and hold each other.”

Her father, although loving and loyal, belonged to a generation that had known many war deaths; they were the survivors who had been severely traumatized by the horrors of war but who had learnt to suppress open expression of grief. “Laugh,” he would say, “and the world laughs with you; cry and you cry alone.”

[...] “However if our view of who we are is based on the idea of our ‘selves’ being part of a commonality of all human experience, (a sense that we are more alike than different) and that we exist as relational beings, then when someone close to us dies, we feel that death as a loss of part of our own ‘self’. I suspect that all those who knew Josh, all those who had any kind of relationship with him, will accept that when he died something inside of them died as well. “

Re-blogged with permission from Jimmy Edmonds at Beyond Goodbye.

Images courtesy of Beyond Goodbye.

Comments