The Whole Truth and Nothing But the Truth

When talking with children about difficult topics such as death, it is much easier to "sugar coat" the truth than it is to be honest. We fear that children "can't handle" the truth, or that they will have a more difficult time with the truth than they would with a more watered down version. We want to protect children from the pain that we experience. The reality is that our lack of openness can sometimes cause more difficulties than the honest truth.

My mother died unexpectedly when I was only 4 years old, and my family did not discuss her death with me. All I knew was that one night Mommy went to bed, and the next day, she was gone forever. As time progressed, my fear of losing others in my life (my dad, my grandmother, my aunts and uncles), began to consume me. It was a struggle for my dad to get me on the school bus in the mornings, and I refused to attend friends' birthday parties or sleep away from home unless he was with me. My family did not understand why I was so terrified to leave my father's side.

My mother died unexpectedly when I was only 4 years old, and my family did not discuss her death with me. All I knew was that one night Mommy went to bed, and the next day, she was gone forever. As time progressed, my fear of losing others in my life (my dad, my grandmother, my aunts and uncles), began to consume me. It was a struggle for my dad to get me on the school bus in the mornings, and I refused to attend friends' birthday parties or sleep away from home unless he was with me. My family did not understand why I was so terrified to leave my father's side.

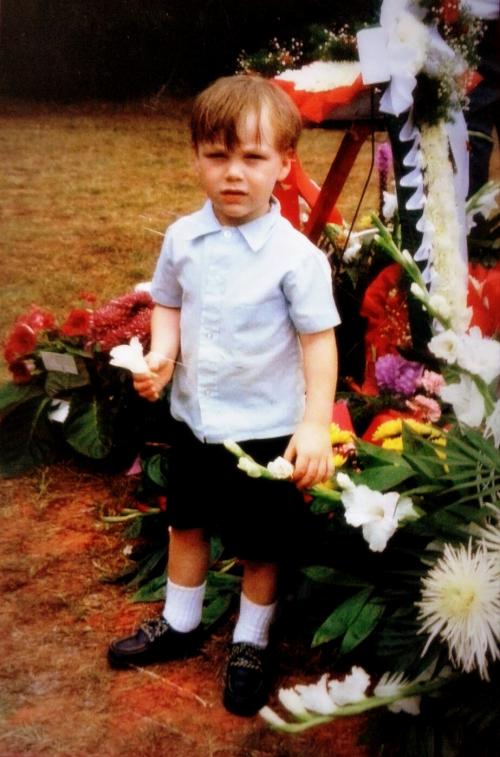

Looking back, the answer seems obvious, especially after such a traumatic loss, but to my grieving family, nothing made sense. The truth is, had someone in my family sat down and explained to me the reality of death, chances are, I would have adapted with less complications. In my mind, "Mommy went to bed and never woke up. The same thing could happen to Daddy, and Grandma, and Uncle Charles..." I attended my mother's visitation and funeral, but no one took the time to explain to me what was happening. For all I knew, we were at a family reunion one day, and at a church service with a bunch of flowers the next.

If children are not told the truth, they begin to create their own realities. We visited my mom's grave occasionally, but for a long time, I believed that my family was lying. When I was finally able to comprehend the idea of death, I denied that my mother had died. I vividly remember visiting her grave as an 8 or 9 year old, thinking to myself, "She's not really here. She just left and no one wants to tell me the truth. She must not have loved me." I never shared these thoughts with anyone, but they could have been easily extinguished had someone sat down and explained to me what had happened in terms that I could understand.

There are a few things I needed to know:

1) That my mother had died.

2) That death is permanent and that we cannot control it.

3) That my mother still loved me.

4) That it was ok to miss my mother.

5) That someone was going to take care of me.

An appropriate response may have been, "Last night Mommy went to sleep. Sometime during the night, her heart stopped, and when someone's heart stops, they die. When someone dies, their body doesn't work anymore. We don't know why these things happen, but what we do know is that Mommy loved you very much, and she didn't want to leave you...but there are some things we can't control. Daddy misses Mommy a lot, and it's ok for you to miss her too. I know this is scary, but no matter what, we are going to take care of you."

These are difficult conversations, and it is important to be selective in how the truth is shared. My rule of thumb is, "Be real, but be sensitive." It is important to speak to a grieving child in terms that he or she can understand. In cases of murder and suicide, it is not always appropriate to be detailed in sharing how the person died, but it is important to help the child navigate the reality and permanence of their loss.

Remember that each child is different, so meet them where they are. Consider the child's cognitive ability, age, support system, and past experience with loss. Focus on their strengths to help them cope and most importantly - be sure they know that they are loved.

Article Images

Comments